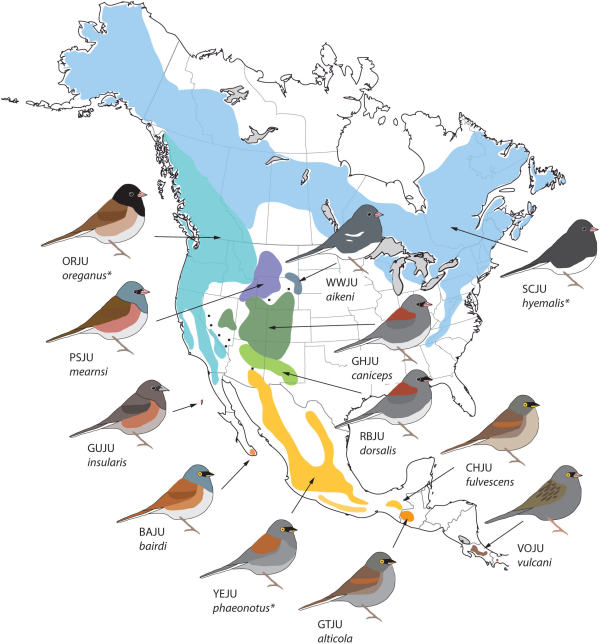

The western Oregon Dark-eyed Junco  The eastern Slate-colored Dark-eyed Junco  The Gray-headed Dark-eyed Junco  Illustration by Borja Mila from the National Museum of Natural Science in Madrid, one of Ellen Ketterson's collaborators, shows the color morphs of Dark-eyed Juncos and Yellow-eyed Juncos across North America.

The seven Dark-eyed Junco color forms

|