A singing Grasshopper Sparrow on territory; photo by Paul Konrad

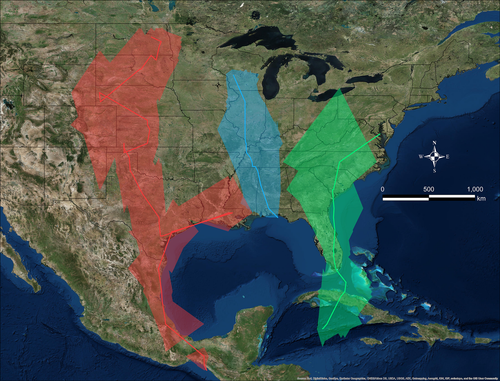

The map shows the most probable fall migration routes for Grasshopper Sparrows from nesting populations in North Dakota (red, 1 bird), Wisconsin (blue, 4 birds), and Maryland (green, 10 birds). Grasshopper Sparrows from the Midwest almost exclusively wintered in Texas and Mexico, whereas Grasshopper Sparrows from the eastern United States wintered in Florida or the Caribbean.

|

New research conducted by Vermont Center for Ecostudies biologists using tiny geolocators sheds light on the annual movements of Grasshopper Sparrows and Eastern Meadowlarks, and yields surprising results that may help transform the way we manage grassland bird populations – across international borders and throughout the birds’ annual cycles. This research fills in fundamental gaps in our knowledge of these species and will pave the way for cooperative endeavors to slow the decline of these grassland birds from the Great Plains to East Coast.

Some migratory grassland birds spend nearly half their lives away from their nesting range, yet we know relatively little about that part of their annual cycle. To investigate the migratory patterns of two important grassland species, the biologists deployed geolocators on 180 Grasshopper Sparrows and 29 Eastern Meadowlarks at Konza Prairie in Kansas, and at 6 Department of Defense installations across the species’ nesting ranges. They were able to retrieve location data about 34 Grasshopper Sparrows and 5 Eastern Meadowlarks.

Vermont Center for Ecostudies biologist Jason Hill explained, “Our research reveals migration routes and specific wintering locations for several populations of Grasshopper Sparrows, and opens the door for a collaborative cross-border approach to managing them year-round.”

Hill continued. “These results are a potential game-changer for re-imagining conservation strategies for these grassland birds.” Grassland bird management has been overwhelmingly focused on improving conditions in their nesting ranges, which is especially understandable for Grasshopper Sparrows that are very hard to find after the nesting season when they’re not singing.

Data retrieved from the geolocators held many surprises. Among the most astonishing information was that Grasshopper Sparrows do not begin fall migration in August as biologists previously assumed; they actually remain in nesting areas until October. The data also revealed that Grasshopper Sparrows make short, nearly daily migration flights, and that the North American Great Lakes region probably serves as a migratory divide for Midwest and East Coast populations.

Conversely, data from Eastern Meadowlarks provided evidence of a diversity of individual movements, ranging from year-round residency in the same location to short- and long?distance migration strategies.

With the support of the U.S. Department of Defense Legacy Resource Management Program, the study revealed where and when these grassland birds migrate each year between nesting seasons: Grasshopper Sparrows from the Midwest almost exclusively wintered in Texas and Mexico, whereas Grasshopper Sparrows from the eastern United States wintered in Florida or the Caribbean.

But Hill explained that many questions remain: “The stopover ecology and non-breeding habitat used by both species, especially for Grasshopper Sparrows in Mexico and the Caribbean Islands, should be a priority for future research.”

For more information about this research project and the Vermont Center for Ecostudies, refer to https://vtecostudies.org/press-release-grassland-bird-migration-patterns/

This research has been published in the scientific journal Ecology and Evolution, Volume 9, Number 1, and can be viewed at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/ece3.4795