After thoroughly enjoying checking in on the loon family every 3 or 4 weeks throughout the summer, it was time for a Fall Update – if the adult loon and fledgling hadn’t left or relocated yet. By the end of September, the fledgling might be left on its own, and having attained flight status, it might relocate to another lake; so there was some question as to whether we would find the loons we had been following through the summer. Already the male appeared to have left by the first of September, which is pretty normal among Common Loons according to researchers contributing to Birds of the World; but that information source also notes that by late September, recent fledglings could be left on their own.

By now the fledgling should be catching all or almost all of the fish it eats daily, and it should be flying occasionally, although it’s been my experience that I rarely see loons fly; so that’s hard to judge, especially when we only check in every 20 days or so. Anyway, I explained to my friend Andy that we may not find “our” loons Thursday afternoon, and we may not find any loons. The other factor for this day was that in spite of planning around weather forecasts, although there was good sunlight – a must – the wind was harsh, a worse-case scenario for photographing on the water. There wasn’t a safety factor to worry about as we boarded Andy’s pontoon boat, but I didn’t image just how bad the wind would be; Saturday would be a better bet according to the weather guessers, but there were a few scheduling concerns that tied us into our Thursday photo session, including homecoming festivities at our nearby alma mater, North Dakota State University – Go Bison!

As I approached Little Pelican Lake, the fall colors were dramatic, nearing peak among the red and orange maples, and yellow and green poplars, ash, and elms, plus the now burgundy sumacs. But there were white caps on the water, small white-capped waves created by a strong south wind in the 30 mile per hour range, so we figured the loons and other birds would probably stick to the more protected south shore and portions of some backwater bays. We headed out and the rough water didn’t seem too bad as Andy kept the pontoon’s engine pressing forward, yet amid the rough surface of the water I totally missed the loons – but Andy didn’t. Indeed, the loons could have been diving and just surfaced, ‘cuz that would be par for the course this windy day.

It appeared that the 2 loons were our adult and fledgling, and Andy motored a half-circle into position with the sun at our back and the loons before us, but by that time the loons were under water and the game of “where are the loons” began. At this point in the season, spending more time below the water’s surface than above it might be part of the normal fishing behavior for the loons, or it may have had something to do with the strong winds and rough water. But Andy soon had his work cut out for him as the loons were clearly on the move, fishing as they swam below the surface, and it became a matter of not only trying to keep up with them, but also just trying to find them in the rough water.

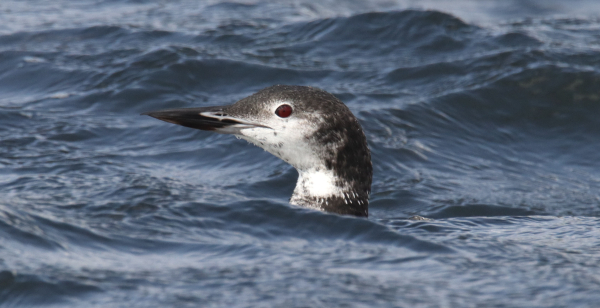

When we did get some closer looks at the loons, it was clear the fledgling hadn’t changed much, as expected; and it retained the attractive tan hue in its plumage. But the female looked to be ¾ of the way through her molt, which was about 40 percent underway 3 weeks earlier. She also seemed to have different “looks” that depended on the direction she was facing, whether from the front, side, or back; but she definitely looked like a different loon compared to her beautiful summer plumage. As we appreciated our first longer, closer look at the loons, it was clear they were immersed in their water world, with waves often covering their body up to their neck, and water droplets adorning their head and body plumage, sparkling in the sunshine.

Big Wave Dave

From the beginning, as I tried photographing the birds it was evident that just keeping them in the photo frame was a new aspect of big wave loon photography. Not only were the waves keeping us bouncing up and down, back and forth, but the magnification of my camera lens was also magnifying the movement caused by the wind-generated waves. The idea of shutting off the pontoon’s engine to stabilize the camera was a mute point with the wild wave action, plus Andy (Dave) needed to counteract the effects of the surf on the boat. My swivel chair also became more of a factor as the boat, wind, and loons created an interesting interplay, and I soon realized the chair could swivel in a full circle, which helped while looking for the loons and while photographing.

Seriously, at points when the loons surfaced in the most open locations, the rocking motion of the boat created a scenario in which one photo would have the head of the loon cut out of the top of the photo frame, and the following photo would have only the head showing above the bottom of the frame. I also noted that few of the photos I was taking were in focus due to the strong wave action, which was concerning. Up to that point, I was photographing using my usual ISO 400 setting, but I quickly switched to ISO 800 to increase the shutter speed into the 1/2000 range using an f-7 aperture. After making that important adjustment, the photos showed much greater potential to be in focus, but the bouncing action on the water created one of the worst percentages of in-focus photographs I’ve ever taken. Even so, amid all the challenges presented by the strong wind, we were having a great time in the moment!

As I said to Andy, I could photograph these loons all day every day – good thing I don’t live on a loon lake I guess. But it sure is a thrill when I visit Andy for a loon photography session! Andy enjoys it too; he enjoys captaining his pontoon boat, although cruising with bird photography in mind takes a different set of skills – positioning the boat with the sun and the birds in mind, keeping the photographer in the closest position rather than having the birds at the back of the boat, turning the engine off and on and motoring as needed. But Thursday, Andy’s abilities were tested, and he definitely rose to the occasion in exemplary fashion – I was really impressed, and Andy got a charge out of it. He noted that he found that often, by keeping the engine in reverse, it helped with positioning the pontoon, and it also helped to keep the boat steadier.

During the course of our 75-minute photo session with the loons, they didn’t seem to react to us – that is, to the pontoon boat – and we enjoyed 2 special extended photo periods with the loons in close proximity, both in locations where there was a bit less wave action. The first such photo period was when the adult seemed to take a break on the surface for a few minutes. I took advantage of the opportunity and took a flurry of photos of her as the sun dodged wind-blown clouds that passed quickly overhead.

The fledgling continued fishing below surface and ended up quite a distance away, but it eventually swam back to the female, providing a number of nice images that showed its tan-ish plumage with beige scalloping (signatory for first-year loons) as it swam in water that had a bit of a golden edge to it – my best photos of the young loon that day. It even provided a full-frame image as it performed a spirited wing flap, which provided the opening photo that illustrates this article. The loons kept a verbal connection throughout our observation period, although their contact calls were louder, perhaps due to the sound of the blowing wind, but they also had more of a loon call quality to them than during the previous photo session, which added to the experience.

The other prime photo period was when the adult took time for an extended bathing session, which took place at the end of our visit. Over and over again she bent into the water and began a flurry of wing flaps that sent a flurry of water into the air, sometimes including some molting feathers that flew up in the breeze. After extended preening and oiling sessions, a couple times she raised up to make a concerted wing flap back and forth to clear water and arrange feathers in proper positions. We stayed near her for an extended period, but knew our time was waning, so left her to continue bathing and preening in the afternoon sunshine.

Each of our 4 photo sessions was different – the conditions, the lighting, the wind, the birds – but that was the idea behind making multiple photo visits – to document the birds under different conditions as the season progressed. Each visit was unique, and uniquely enjoyable; and the resulting photographs will be among my favorites. I hope you’ve enjoyed seeing the images, and I hope the information shared has been helpful, even inspiring. Certainly anyone can create a similar series of photos of seasonal bird activities; and that kind of series can evolve from humble beginnings when you didn’t intend to follow a period in the life history of a bird or a species. The loons provided a rewarding opportunity and a memorable collection of images – Hoooray for the state bird of Minnesota!

Article and photographs by Paul Konrad

Share your bird photos and birding experiences at editorstbw2@gmail.com